Deliver

No product is ever designed right the first time around. Arguably, products are never really done. The purpose of prototyping is to learn, to observe. To fail fast, in order to improve the product before it launches to the general public. In essence, it's like a tiny (sometimes internal) beta test. They are a user-tested proof-of-concept. David Perell wrote something that resonated with me in the context of prototyping.

“The Internet rewards people who learn in public”

- David Perell (on Twitter)

By showing our work early, by sharing a prototype or running a (public) beta, we learn in public. We're able to obtain feedback sooner, which means we're making a product that users love sooner.

Prototypes as a boundary object

Yang (2005) describes how prototypes are part of design language, because prototypes represent and embody design thought. In a similar groove, Sanders & Stappers (2014) describe the roles of prototypes in research through design.

- Prototypes allow testing of a hypothesis.

- Prototypes bring practise and theory together and force those involved to deal with confronting perspectives, theories and lenses.

- Prototypes evoke focused discussion in a team because the phenomenon is ‘on the table’. By demonstrating, we create a common understanding of the proposed solution.

- Prototypes act as a way to connect to our users, they allow us to explain a concept effectively, by creating an equal reality to learn about.

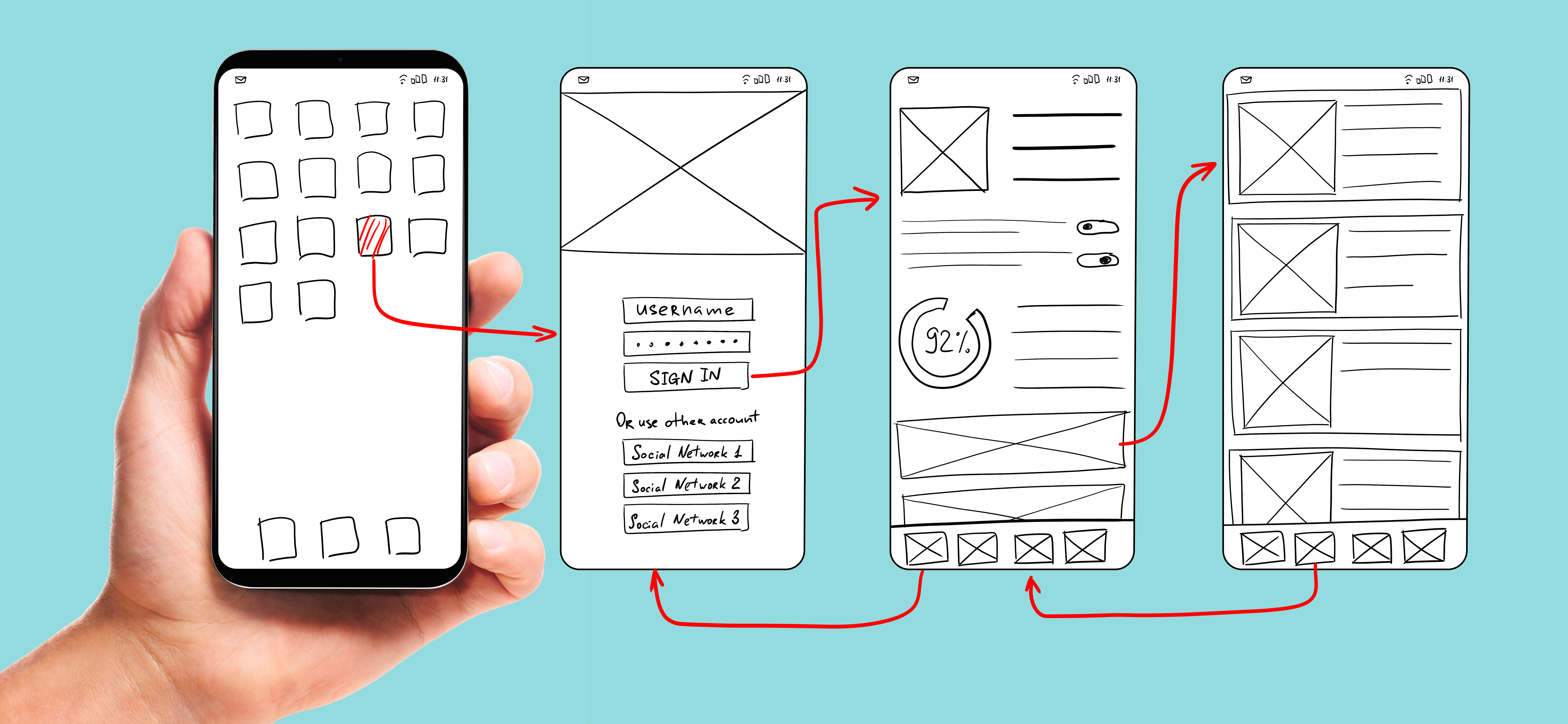

Different levels of prototyping:

When creating prototypes it's crucial to understand what we want to learn. Low fidelity prototypes are easier and cheaper and allow for quick iteration, whereas high Fidelity prototypes are much closer to the final product. The drawback is that they are more time-consuming and costly.

Low fidelity

- Low cost, rough and quick to build

- Easier to execute and less costly

- Early stages of a project

- Test many assumptions quickly

- Easy to get feedback on, since people *see* you're in early stages

- ex. paper prototypes, paper models, simple or rough sketches

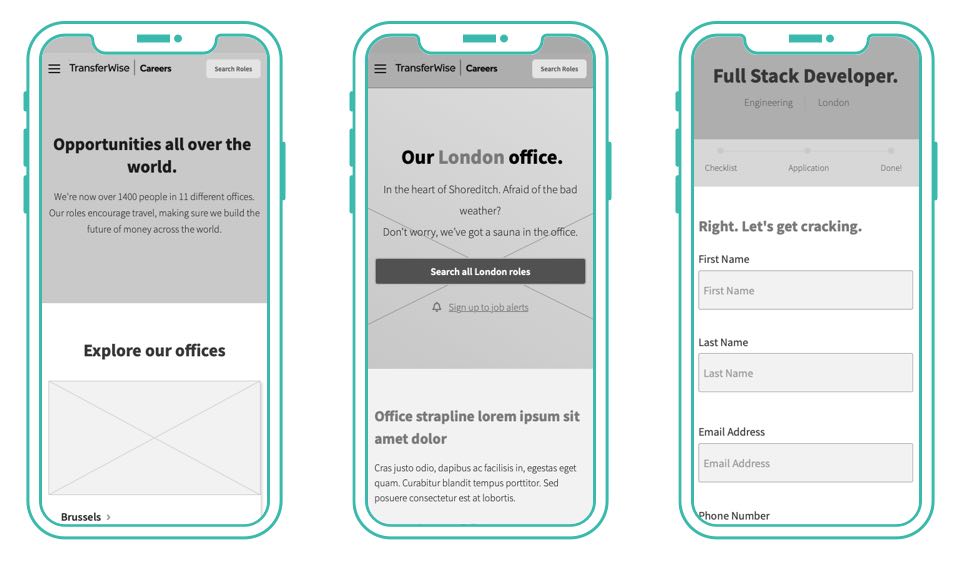

Medium fidelity

- Slightly more detailed, still rough but closer to the solution

- Take longer to develop and costlier

- Prototyping phase towards refinement

- Make them resemble final products more closely

- Give people a better sense of what the solution might look like

- ex. wireframes

High fidelity

- Much closer to final, very detailed and much more time-consuming

- Provide an accurate representation of what the solution might look like with fine details

- They may include much of the expected functionality

- We may execute these using less-than-optimal mechanisms or technology

- Closest representation of the idea possible without the time and cost required of final production

- Ex. Mock-ups, coded prototypes

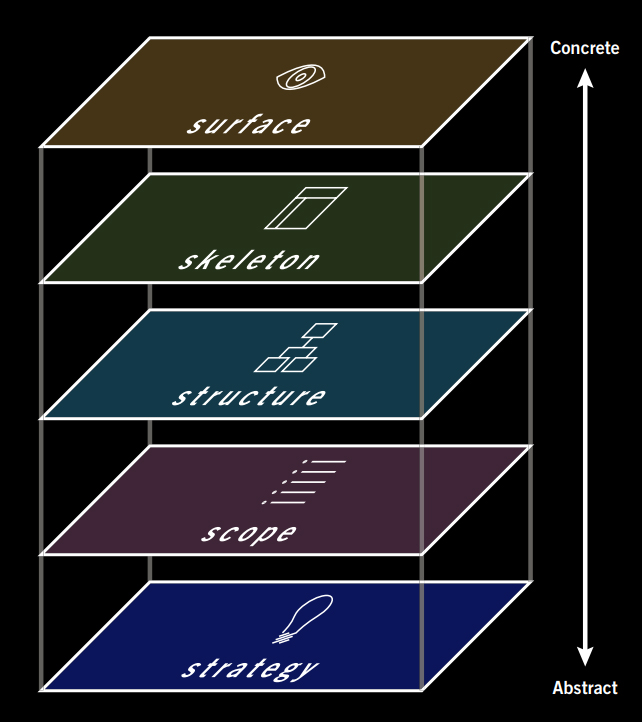

The five planes of experience design

Jesse James Garret (2011, pp. 19–22) describes the elements of experience design as the five planes; surface, skeleton, structure, scope and strategy. They provide a framework for talking about user experience problems. Building from the bottom, the issues we have to solve become less abstract and more concrete.

- Surface: Visual design

- Skeleton: Interface, navigation and information design

- Structure: information architecture & UX Design

- Scope: Content & feature requirements

- Strategy: Business Objectives and user needs

Chris Callaghan (2020) combined this to create a framework for effective prototyping. His framework describes how the fidelity of prototyping can be tuned on each of the five planes. The result is a matrix that describes how big the impact of these types of fidelity have on each of the functional layers.

| Type of fidelity/functional layer | Strategy | Scope | Structure | Skeleton | Surface |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual fidelity | low | low | low | low | high |

| Functional fidelity | low | low | low | high | high |

| Content fidelity | low | low | high | high | high |

Evaluate

When evaluating prototypes, it's important to ask both novices and experts. While experts show a wider range of issues, the problems are generally perceived as less severe. they generally know how to work around issues. Novices experience issues as more severe, but find fewer in total (Sauer, Seibel and Rüttinger, 2010).

Usability

Knowing which problems to focus on can be a big problem. There's been some research to categorise the severity of the issues users describe. Jakob Nielsen defines a set of metrics to define usability severity (1994) which focuses our attention to the worst offenders. To gain quantitative data to act on, Matt (Kendall, 2020) likes to use heatmap tools (like Hotjar). They record users' actions which help identify usability issues.

Click the button to toggle on a heatmap of your activity on this page:

Note: This data is entirely local and never leaves your computer (I won't be able to see it)

Content strategy

Experience goes far beyond the actual product we're designing. Matt (Kendall, 2020) describes how content strategy should be considered part of the experience equally. Consider the importance of something like the box a product comes in. When buying a product, all else being equal, customers will opt for the business that sends products in a recycled box with a golden bow. Matt tells us how he's particularly intrigued by physical touchpoints of digital challengers like Warby Parker and Ace & Tate. Even their stores offer a better experience than 'legacy' counterparts by integrating their digital systems into the buying experience. They offer services like order-from-home emails after an eye measurement, which provides an overall better experience for the customer.

Beyond Experience

Content strategy focuses on content that creates an experience, rather than how to market that experience. However, there is a lot that we can learn from the marketing industry (UXBooth, 2016). Content strategy is aiding the digital sophistication of businesses, to improve the customer experience. Beyond that, it is also an opportunity for 'always on' data collection. In summary, content strategy is about:

- Automated content to offer a better experience

- Ongoing optimizations and upgrades, through always-on data collection

- Aiding digital sophistication of brands

In Practice

As a result of our insight, a little feedback by PVH and going through ideation, we developed our first idea and prototype. These prototypes iteratively improved on the idea of digital fashion. Contradictory to what we had learned about effective prototyping from Chris (Callaghan, 2020), I created high (visual) fidelity prototypes. Mainly because I wanted to try Framer, which proved to be a useful addition to my prototyping toolkit.

Note: This report and our digital and online handover package to PVH was built in React with Next.js, which I've used for coded prototypes before as well.

1. Wearby — Digital Subscription Wardrobe

A digital wardrobe with digital trendy clothes and a subscription to use exclusive pieces.

The endless possibilities of digital fashion were recognized by by our research participants on Ping Pong. Though they wouldn't immediately see themselves spend a monthly subscription to use the service.

2. Digital Fashion Hunt

Our next prototype was about creating an experience around digital fashion. An AR treasure hunt to find digital clothes around the world. They can be found at specific places around the world and can be traded globally. Connecting people, brands and places together.

Upon testing this prototype, we realised people see fashion as content. Many want to share a story when they share photos of their clothes. This is clearly an effect of a strong emotional experience, one we decided to take a step further for our last iteration.

3. Manifest — Digital Fashion for Social Good

Our third and final prototype and the solution we presented to PVH is our concept Manifest. Manifest is a digital fashion platform for real-life social impact. Connecting causes and an endless wardrobe, so what you wear becomes a statement.

We would like to see a variety of products on Manifest, with a variety of use cases, created by different entities:

- We imagine big brands could sample their ideas digitally, to test user adoption before they start fabrication.

- We envision independent digital fashion artists like PassGoalTriple reaching a larger audience with their experimental creations.

- We imagine that established brands would like to put out certain products for free, connected to an AR experience that drive social impact through their name.

- We want people not only to donate to causes they care about, but be proud to show their support, by giving them a digital artefact to represent that.

We’re also promoting the idea of swapping digital clothes with the community, which we hope will entice people to do so in real life too.

Critical Review

I described a few prerequisites for Manifest to technically succeed in the handover package we sent to PVH. First off, it's good to know that commercial 3D rendering engines (Unreal & Unity) support AR and even dedicated AR tools like Instagram's SparkAR exist. These tools lower the barrier to market and make developing basic filters trivial.

Digital clothes however brings a few new issues, currently requiring manual labour. These issues are caused by three factors:

- Variety of body types and sizes

- Correctly blending filters with the subject and background

- Flexible textures responding to body movement

In short, these issues can be solved by developing parametric fashion design, applying subject separation AI and developing real-time cloth simulation tools. These issues aren't easy to solve, but our recommendations provide PVH with a basic roadmap towards our digital fashion future.