Introduction

My background is in Industrial Design Engineering, which I was taught at the Delft University of Technology, a university known for its methodical design practice. A common way of breaking down the design process for us was Roozenburg & Eekels' Basic Design Cycle (1995, pp. 84–93). At Hyper Island, I was finally introduced to Design Thinking and the Double Diamond Model. While I had often heard of these terms, I had never applied them myself. In many ways, these frameworks towards innovation overlap, the differences, however, are telling.

Digital Agility

Digital design has the benefit that it's highly flexible. After a product is launched, it's easy to rework or even repurpose (pivot) the product. As Basecamp's Jason Fried said:

“You can only iterate on something after it’s been released. Prior to release, you’re just making the thing. [...] So if you want to iterate, SHIP.”

- Jason Fried (source)

Industrial design, originating from Mechanical Engineering, is centred on products with a physical component. Experimentation is comparatively expensive (consider the price of injection moulds, manufacturing plants and distribution) and as a result, physical products don't enjoy nearly the same agility as digital ones. The flexibility of digital products is a luxury I've come to appreciate a lot in my experience with digital products. Knowing this, it's easy to see why the Basic Design Cycle (Roozenburg and Eekels, 1995, pp. 84–93) is much more focused on setting and evaluating criteria than design thinking. There's an explicit feedback loop that improves the product until the design is approved. This was only added later to Design Council's Double Diamond (2019). It's clear that design processes are ambiguous and neither model is correct or wrong, but both provide a good methodical starting point in their industry.

Double Diamond Revamped

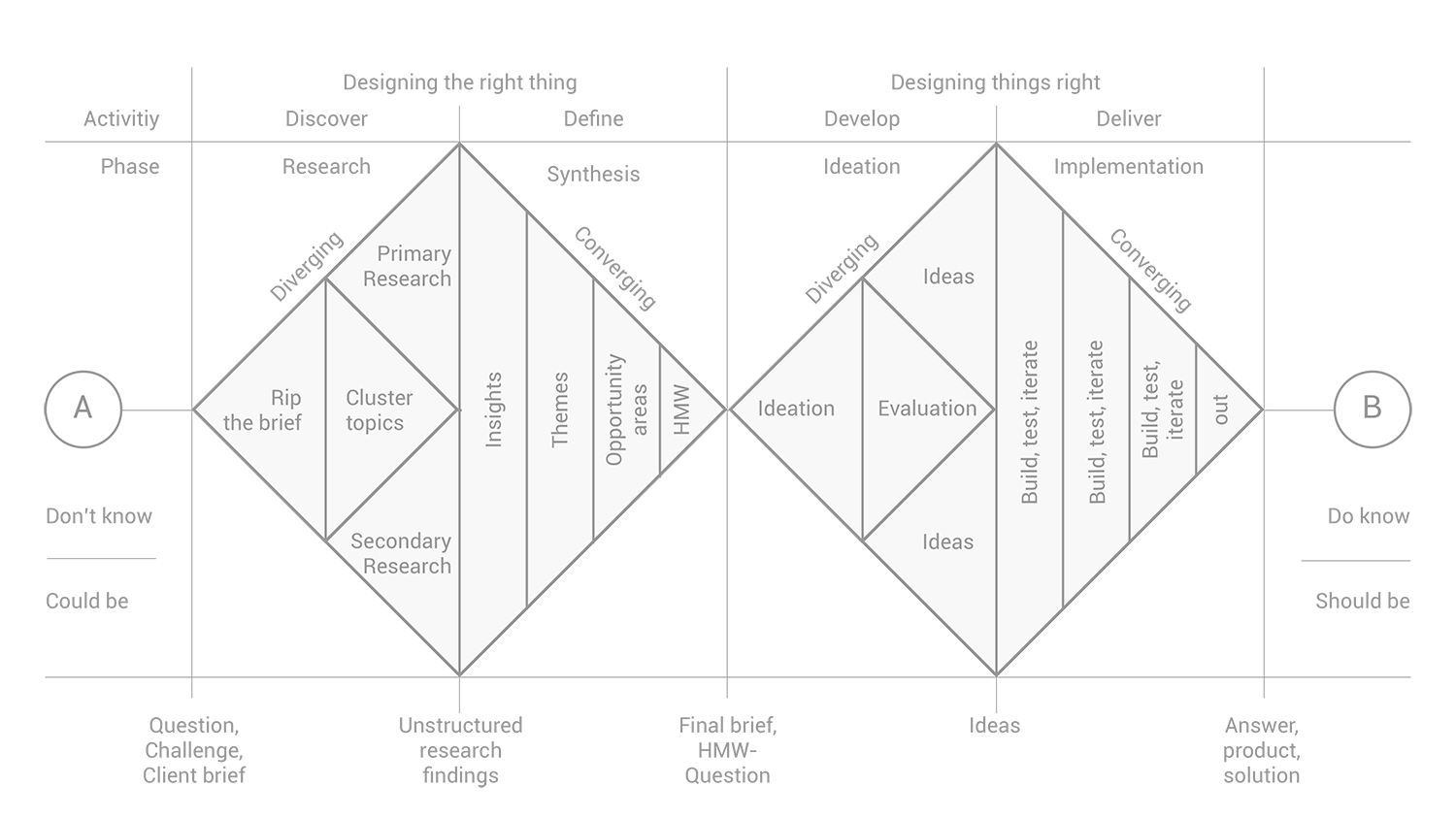

My favourite take on the Double Diamond, The Double Diamond Revamped by Hyper Island Alumnus Dan Nessler (2016) offers a lot more depth than the original by the British Design Council (2019). It shows how within each diverging phase, there can be converging sub-activities and vice-versa. On top, it shows the purpose and the expected results of each phase too, offering a lot of clarity to people new to design.

Vision within Reason

Hekkert and van Dijk, explain in their book Vision in Design (ViP) (2011, pp. 128-129) how a design process is a balancing act between forward-thinking, visionary, inspiration and making reasonable decisions.

“Give room to feelings and intuition as they do at art schools, but simultaneously develop a sound argument in order to justify and explain each and every decision they make.”

- Paul Hekkert & Matthijs van Dijk (2011, pp. 128-129)

While ViP is a very different process compared to the Double Diamond model, the goal is to a large extent similar. It attempts to project us into the future, by breaking down the context we live in (or in ViP's case, expect to live in). The goal is to inspire and educate us about the problems worth solving. Identifying how these problems influence people's lives comes with an understanding of the way people live experiences in general.

Experience

First of all, it's important to be aware that experiences are not self-contained, they happen inside a larger context and are greatly influenced by the way individuals perceive them. As Peter Benz puts it:

“Experiences emerge in the intertwinement of a variety of objects, interactions, spaces and information.”

- Peter Benz (2015, pp. 32)

Benz describes how lived experiences are a result of a moving intersection between sense, consciousness, body, and the world. An approach for experience designers, as such, could focus on thinking, sensing and feeling. Though, it's important to remember that these elements can't be seen in isolation either, in actual experience they are deeply entangled as well. When we do design research we have to understand that everyday experience is continuous, seamless and endless, we're only trying to understand a small slice of that.

Experiences are influenced by differences far-reaching like our marital status, to mundane differences like the operating system our phone is using. How we design for these differences is driven by design research.

(Look, I'm not pretending this is useful information, I'm just doing some mood-setting here.)