Define

Designers often describe their work as organizing complexity, to find clarity in chaos (Kolko, 2010). During synthesis, we often manipulate data, words and pictures, to create cohesion and a sense of continuity in our work. The define phase is everything that pushes towards the organization, reduction and clarity. Synthesis is often described as the most elusive and hardest part of design.

“Good design is as little design as possible”

- Dieter Rams (2019)

Sense-making

This phase intends to make sense of our research data. Before we're able to develop new ideas we have to prioritize which problems our users have most (or most often) trouble with (Anderson and DScout, 2019). Structured data also enables us to communicate better with each other, as well as outside stakeholders.

Magic of Design

Many aspects of design are visible activities and easy to grasp even for non-designers. They are easily understood by watching our idols. Synthesis is often a lot more solitary and completely hidden as a result. Some (good) designers have magical status because synthesis is often performed privately (Kolko, 2010).

“A good designer can create normalcy out of chaos.”

- Jeffrey Veen (2001, pp. 104)

Only after ideation has started the work becomes transparent again. The result is designers often have trouble communicating the value of their insights due to a lack of transparency.

“When synthesis is conducted as a private exercise, there is no visible connection between the input and the output; often, even the designers themselves are unable to articulate exactly why their design insights are valuable.”

- Jon Kolko (2010)

Co-design

Design synthesis has not drastically changed since Kolko's analysis. Nonetheless, there has been a sizeable body of research drawing attention to the transition from individual to group-level sense-making. Supporting verbal exchanges and cognitive processes in collective sense-making (Stigliani and Ravasi, 2011) .

Insight

Data becomes useful to the design process once we start to see themes. To find themes in a vast amount of data, designers should analyse word repetitions and analyse metaphors and analogies (Yuan and Hsieh, 2015). This is what we call insight. Arunima, design researcher at IDEO, says design research is more than describing the now, it's about inspiring the next (Duque, 2020). She describes insight as: “a gut-felt response that makes you sit up and think”. It changes our opinions and consequently how we solve a problem. Spotify's Adrian Buendia is a bit more pragmatic, he said:

“[F]or us the real magic is in the insight — the interpretation of that information”

- Adrian Buendia (2020)

Perspective

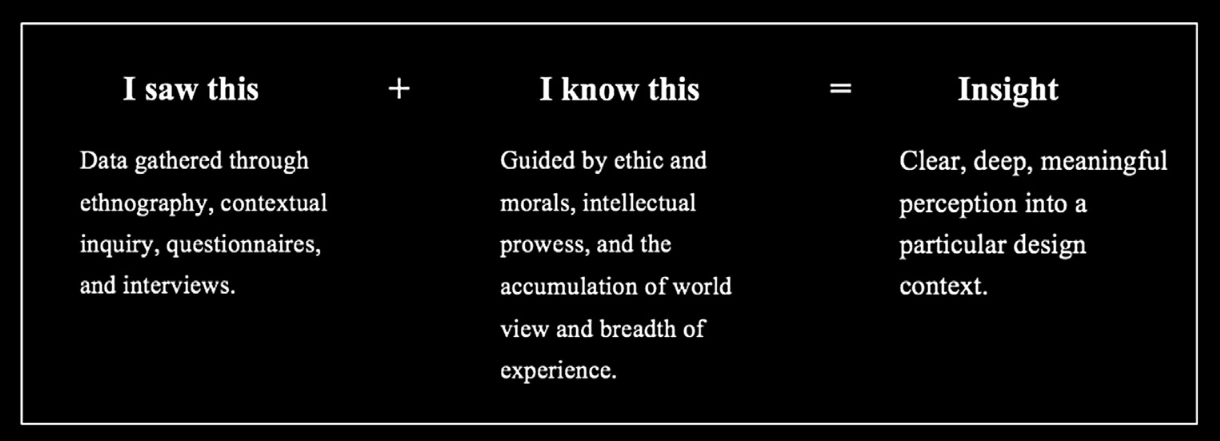

Even insight generation is a function of personal experience. Yuan & Hsieh (2015) describe how insight is the result of an observation, influenced by current knowledge (epistemology).

Data gathered through during discovery are guided by the researcher's ethical standards and morals. Their intellectual prowess and the accumulation of world view as well as the breadth of their experience.

In Practice

Throughout the project we used several techniques to (collaboratively) make sense of the context we were working in. With the vast amounts of data we produced it was easy to get lost, but several tools helped us see the red thread in our work.

Interview Downloads

Digesting our 20+ thirty to sixty minute interviews provided quite a challenge. Interview downloads (Duque, 2020) are a great way to collaboratively summarise our results. Afterwards they were easy to share with the team, which proved necessary because some of our interviews were in Portuguese and Russian.

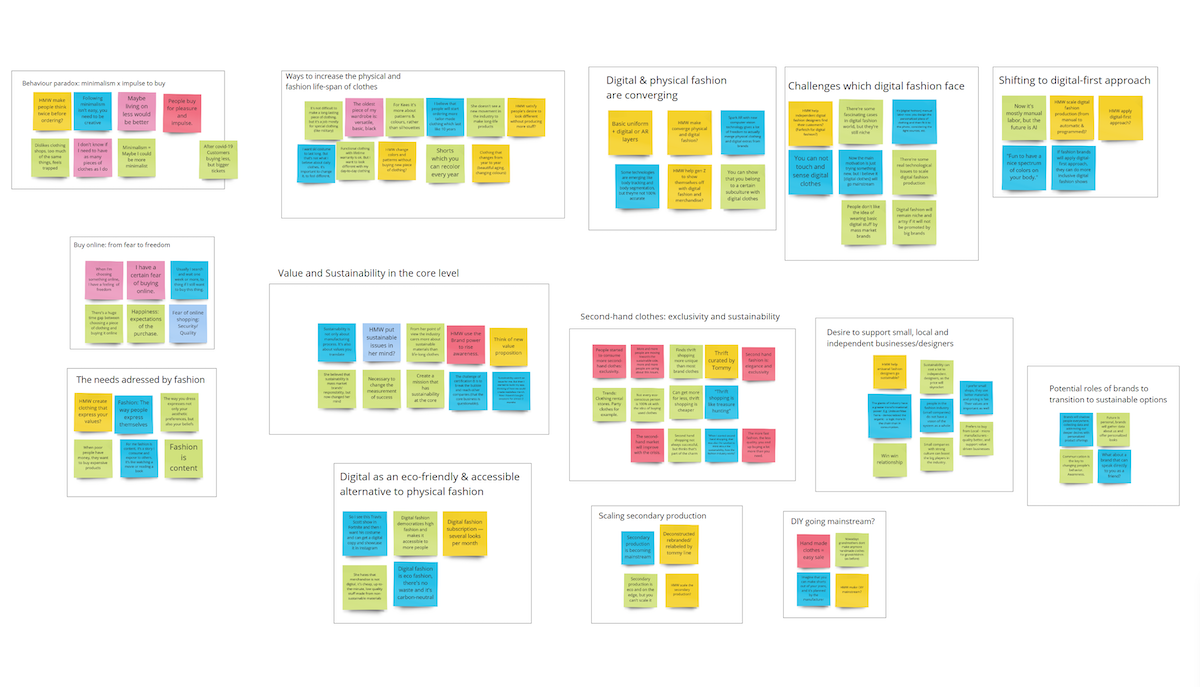

Affinity Mapping

Our business, industry and interviews all came together in an affinity map. We clustered our digital Post-It's™ and described what themes they signify.

Personas

We used personas to combine similar user needs, habits and attitudes to make our user research more digestible. They communicate the nuanced commonalities and differences between Spotify's users (Karol, Hörding and Torres de Souza, 2019). These personas were created for our project for PVH, have a swipe!

A common pitfall to personas is that they become one-dimensional, hypothetical stereotypes (Baltazar and DScout, 2019). Personas aren't supposed to be a caricature, they exist to create empathy, to remind us of who we spoke with and who we're designing for. As our research advanced, our personas also developed.

Key findings

Despite the rise of the sustainability movement:

- The majority of fast fashion lovers still want cute, cheap outfits that look great on Instagram

- Those who are concerned by environmental issues, still desire a different look every day, they don’t really want clothes that last long

Although we tried not to be driven too much by technology, we saw a clear opportunity; fashion designers are exploring digital clothing. We went into ideation guided by the following statement:

How might we make people feel they have an endless wardrobe without owning stuff?